Glenn T. Seaborg Biography

1912 – 1999

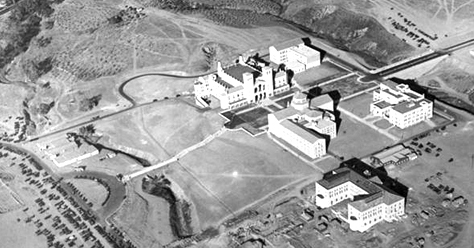

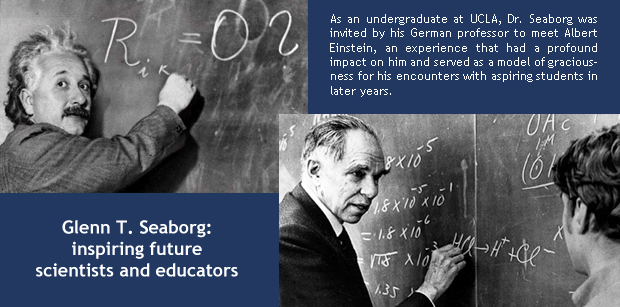

Glenn T. Seaborg was one of the most remarkable and influential chemists of the 20th Century. Born in 1912 in Michigan, he came to Los Angeles at the age of ten. After completing undergraduate studies in Chemistry at UCLA in 1934, he began graduate work in nuclear chemistry at Berkeley and received a Ph.D. in 1937. He joined the faculty at Berkeley as instructor in 1939. Dr. Seaborg’s lifelong research effort was directed toward the radiochemical synthesis and characterization of elements. He and his coworkers discovered ten transuranium elements and many isotopes that have applications in research, medicine, and industry. In 1951, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. After serving as Director of the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory from 1946-58, he accepted the position of Chancellor at UC Berkeley. In 1961, he was named Chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, a position he held for ten years. Dr. Seaborg played a key role in the conclusion of the treaty that banned the testing of nuclear weapons in the atmosphere. He was the recipient of many awards, including the National Medal of Science and the Enrico Fermi Award, and held the unique distinction of having element 106, Seaborgium, named after him. He remained active in research, education, and public service until his death in February, 1999.

Dr. Seaborg studied chemistry at UCLA from 1929 to 1934

Below are excerpts from a diary that Dr. Seaborg kept while he was an undergraduate at UCLA. He received a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from UCLA in 1934.

Below are excerpts from a diary that Dr. Seaborg kept while he was an undergraduate at UCLA. He received a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from UCLA in 1934.

Friday, August 30, 1929. Worked at Firestone, 9 hours (graveyard shift). Told Dr. Stanley that I intend to quit my job at Firestone to start UCLA as a chemistry major. He tried hard to convince me to stay on my job at Firestone, hinted he could give me a raise if that is an issue. I told him I was determined to start at UCLA this fall…

Friday, September 20, 1929. 8:00 a.m. Cut lawn. Got a haircut. Had reading by Dr. Miller, a phrenologist, in Los Angeles. He diagnosed me as fitted for a career in science…

Monday, September 23, 1929. 6:20 a.m. My UCLA classes begin today. My first class was at 9 a.m., College Algebra with Professor Whyburn, and my second class was at 10 a.m.; Chemistry 1A in the auditorium of the Chemistry Building with Professor William Conger Morgan, a formidable man. When Professor Morgan strode into the auditorium he glowered at the full room of some 300 students. He finally broke his silence to announce in a stentorian voice: “Look at the student on your right. Look at the student at your left.” After we had all done this he bellowed “One of you three will not be here at Thanksgiving time.” This was followed by German A, at 11 a.m. Bought books, brief case, fountain pen and ASUC book…

Friday, August 10, 1934. 8:00 a.m. Bought a suitcase in Los Angeles. Finished packing and left for Berkeley from the Los Angeles Railroad Station on the 6 p.m. owl train. This probably means I have left my parents’ home in South Gate permanently.

1934 to 1961 – Dr. Seaborg rose from graduate student to faculty member, eventually becoming the second chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley

Dr. Seaborg earned his Ph.D. from UC Berkeley in 1937 and joined the chemistry faculty there in 1939. He started his collaboration with E.M. McMillan (with whom he shared the Nobel Prize) in 1940. Dr. Seaborg was named professor of chemistry in 1945. He became the Associate Director of the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory in 1954. Dr. Seaborg continued in that position while he served as the second chancellor of UC Berkeley until 1961. He worked away from Berkeley during two significant periods: once to participate in the Manhattan Project at the University of Chicago from 1942 to 1946 and then again to chair the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) from 1961 to 1971 — from which he returned to Berkeley.

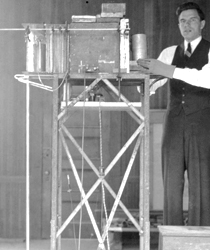

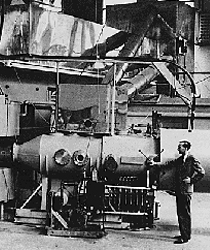

(Left) Dr. Seaborg at his Ph.D. graduation ceremony at UC Berkeley in 1937. (Middle) Dr. Seaborg in the East Hall on the UC Berkeley campus in 1937 with neutron scattering apparatus. (Right) Nobel Laureate Dr. Ernest Lawrence with Dr. Seaborg in early 1946 at the controls to the magnet of the 184-inch cyclotron, which was being converted from its wartime use to its original purpose as a cyclotron. Dr. Lawrence, a Professor of Physics at UC Berkeley, had a huge influence on Dr. Seaborg’s life. The cyclotron that he invented in 1939 (see below) was used by Dr. Seaborg to discover plutonium and his secretary, Helen Griggs, married Dr. Seaborg in 1942.

In 1941, Dr. Seaborg’s research led to the discovery of plutonium and to the last major change to the Periodic Table of the Elements

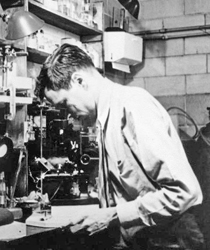

(Left) The 60-inch cyclotron at the University of California Lawrence Radiation Laboratory that Dr. Seaborg and his colleagues used for the discovery of plutonium in 1941. The machine was the most powerful atom-smasher in the world at the time. (Middle) Despite its toxic reputation, plutonium radiates alpha particles, which do not have enough energy to penetrate skin or clothing, let alone cardboard. This meant Seaborg could carry samples of his discovery in a cigar box such as the one above which is now at the Museum of History and Technology at the Smithsonian Institution.(Right) Dr. Seaborg looking at the first pure plutonium. About the discovery he told the Associated Press in a 1947 interview: “I was a 28-year-old kid and I didn’t stop to ruminate about it. I didn’t think, ‘My God, we’ve changed the history of the world!'”.

Dr. Seaborg contributed to the discovery and isolation of ten elements, developed the actinoids concept and was the first to propose the actinoids series which led to the last major change to the Periodic Table of the Elements in 1941. (Middle) Dr. Seaborg holds a gift sculpted by a fan. (Right) The ion-exchanger illusion column of actnide elements in 1950

From 1942-1946, Dr. Seaborg headed the plutonium work of the Manhattan Project at the University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory

With the entry of the United States into World War II, the U.S. initiated a massive effort, the Manhattan Project, to create the first atomic bomb. In 1942, Dr. Seaborg was recruited to head one section of the project, to be carried out at the University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory. (His discovery of plutonium critically contributed to development of the atomic bomb).

Nazi scientists had already discovered the principles that make an atomic bomb possible and time was of the essence. “We worked twelve hours a day, six days a week.”, Dr. Seaborg wrote, “I was hospitalized from exhaustion, but languishing in bed provided no relief. The doctors could do nothing, but finally released me when I made my fever disappear by removing the thermometer when the nurses weren’t looking.”

Dr. Seaborg remembered, “I had helped create the most destructive manmade force ever known. But I was convinced that the atom had even greater potential for peaceful uses. Kennedy was offering me a powerful forum to promote these benefits and for the all-important work of arms control.” Although his name is forever linked to plutonium’s use in atomic weapons, Dr. Seaborg was an ardent advocate of nuclear disarmament for the rest of his life.

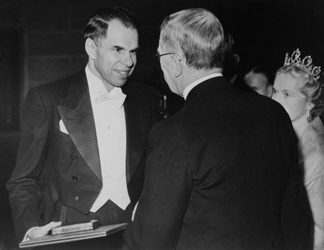

In 1951 Dr. Seaborg (with Dr. Edwin McMillan) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

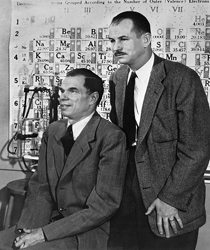

(Right) Dr. Seaborg accepting the Nobel Prize from the King of Sweden in 1951. (Right) Dr. Seaborg with Dr. Edwin McMillan. Together they were awarded the Nobel Prize in Science for discoveries in the chemistry of the transuranium elements

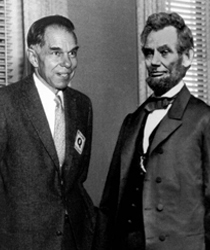

During his career, Dr. Seaborg was advisor to ten U.S. presidents

(Left )Thanks to digital magic, Dr. Seaborg appears to have even met President Abraham Lincoln. (The manipulated photo was created for Dr. Seaborg’s 81st birthday.) (Middle) In 1944, Dr. Seaborg and his wife Helen attended the campaign rally for President Franklin D. Roosevelt in Chicago where this photo was taken. Although Roosevelt was familiar with Dr. Seaborg’s work, they never met personally. (Right) Dr. Seaborg and other members of the first President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) with President Dwight Eisenhower in 1960

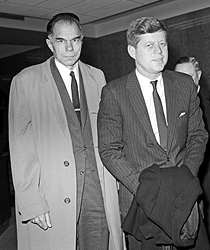

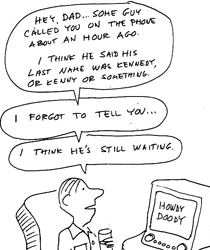

In 1961 Dr. Seaborg was asked by President John F. Kennedy to serve as the Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) which he did through the 60’s and 70’s under Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. (Left) Dr. Seaborg and President Kennedy, following the President’s visit to the AEC headquarters. About the cartoon (Middle), Dr. Seaborg reminisced, “I was in direct contact with President Kennedy (sometimes we met nearly every day); one time he called me (at home), and one of my young sons answered the phone and he got distracted and didn’t get around to telling me until some time afterwards. Finally I went to the phone, and there was President Kennedy at the other end of the line patiently waiting for me, and he went on to whatever he had to say.” (Right) Dr. Seaborg and President Kennedy during the president’s visit to the Nevada Test Site in 1962.

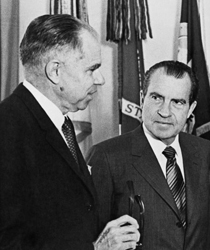

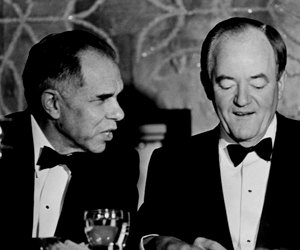

(Left) In 1965, Dr. Seaborg with President Lyndon Johnson and President Harry S. Truman. (Middle) Dr. Seaborg and President Richard Nixon in 1970. (Right) Dr. Seaborg and President Lyndon Johnson have a private chat in the White House Oval Office in 1973.

(Left) Dr. Seaborg introducing then Vice President Ford at the World Future Society in 1974. (Middle) Dr. Seaborg with President Jimmy Carter at the 24th Annual American Academy of Achievement’s Banquet of the Golden Plate Salute to Excellence in 1984. (Right) Dr. Seaborg briefing President George Bush on “cold fusion” phenomena at the White House in 1989.

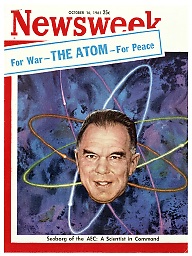

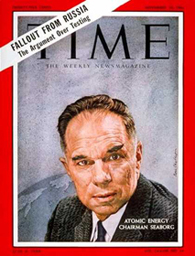

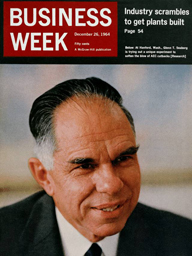

As the Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) from 1961 to 1971, Dr. Seaborg was in the media spotlight

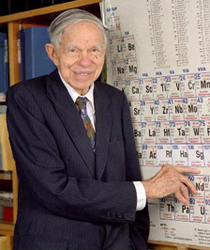

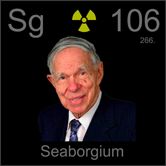

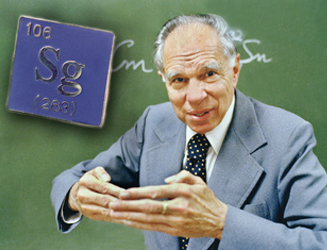

In 1994, Dr. Seaborg became the first living scientist to have an element named in his honor

In 1994, the element with the atomic number 106 was named seaborgium in Dr. Seaborg’s honor, marking the first time an element was named for a living person.

Element 106 was discovered almost simultaneously by two different laboratories. In June 1974, a Soviet team of scientists at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research reported producing an isotope with mass number 259 and a half-life of 0.48 s, and in September 1974, a research at UC Berkeley reported creating an isotope with mass number 263 and a half-life of 1.0 s. Because their work was independently confirmed first, the Americans suggested the name seaborgium to honor the Dr. Seaborg.

About the naming, Dr. Seaborg wrote, “This is the greatest honor ever bestowed upon me–even better, I think, than winning the Nobel Prize. Future students of chemistry, in learning about the periodic table, may have reason to ask why the element was named for me, and thereby learn more about my work.”

Dr. Seaborg’s many awards and honors earned him a spot in the Guinness Book of World Records as the person with the longest entry in Who’s Who in America

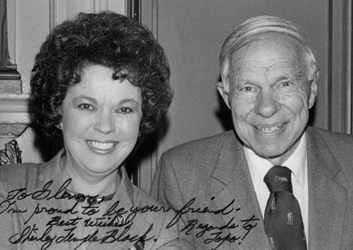

During his career, Dr. Seaborg met many fascinating people

Dr. Seaborg credited much of his success to his wife Helen’s valuable advice and assistance

In 1939, Dr. Seaborg met and fell in love with Helen Griggs, the secretary of his campus colleague at Berkeley, Nobel laureate Dr. Ernest O. Lawrence, inventor of the cyclotron. They wed in 1942 and had seven children. Their family is pictured here in 1964. She was an active advocate of child welfare and an avid hiker. Mrs. Seaborg passed away in 2006 at the age of 90.

“There is beauty in discovery. There is mathematics in music, a kinship of science and poetry in the description of nature, and exquisite form in a molecule. Attempts to place different disciplines in different camps are revealed as artificial in the face of the unity of knowledge. All illiterate men are sustained by the philosopher, the historian, the political analyst, the economist, the scientist, the poet, the artisan, and the musician.”

Dr. Glenn T. Seaborg in 1958, upon being appointed Chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley

Yearning to learn more about Dr. Seaborg? Visit these websites: